Relating Roman Rings: layman’s talk (translation)

Open presentation slides in new tab

Introduction

“Dear Rector, dear audience”.

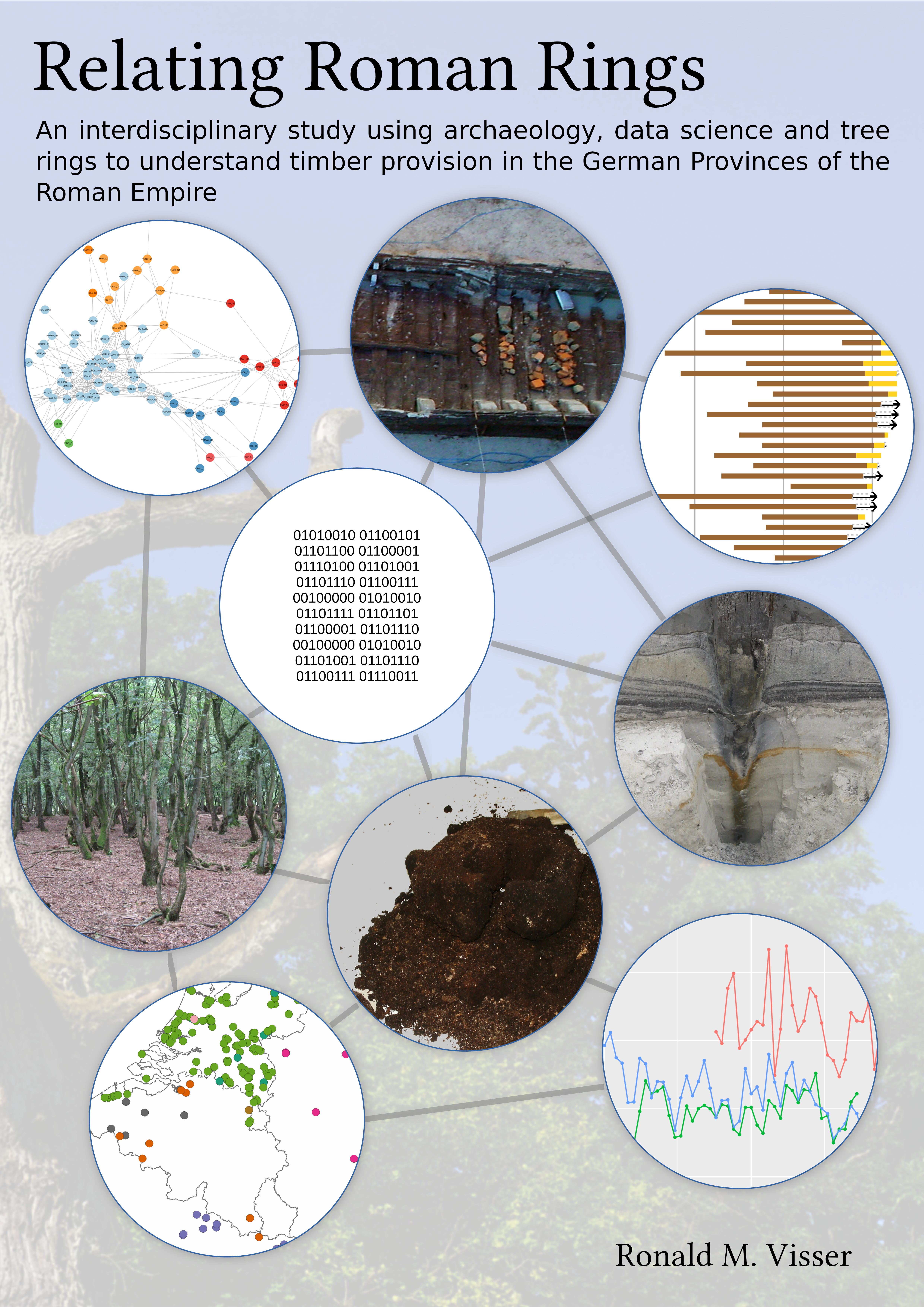

Welcome family, friends and colleagues. Today I will defend my dissertation (slide01) “Relating Roman Rings. An interdisciplinary study using archaeology, data science and tree rings to understand timber provision in the German Provinces of the Roman Empire” (Visser 2025). I now have 10 minutes to succinctly and comprehensibly explain the work of years. I will do my best to shortly explain 366 pages with a number of slides.

I have been researching wood in Roman times, focusing specifically on production and origin of wood. Why wood? Wood is one of the most important raw materials in Roman times, as well as today. After all, you can make anything from wood (slide02). For example, we know from Roman times (slide03) wooden boats and barges, wooden wells, wooden foundations, but also the construction of bridges and roads required a lot of wood. Not to mention small utensils or the use of firewood.

In the Netherlands and surrounding areas we find a lot of wood during archaeological excavations and that makes Dutch archaeology very special, because wood is our archaeological gold. We have in our country a unique soil archive with many organic materials (slide04, for example the only known complete span saws come from De Meern and we have excavated beautifully preserved ships or complete infrastructure founded on wooden piles. This gives us a unique insight into past material use. What we don’t know, however, is where all that wood came from. We know the archaeological sites, but not where the trees grew and if and how they were cared for. Did they get the wood from the forest around the corner? Or was wood transported long distances? And what caused this?

Data used

To investigate this, I used existing data (slide05), such as archaeological data, year-ring data, historical data, spatial data and, for example, inscriptions. Because of the amount and diversity of data, I had to use (methods from) different disciplines. As a result, an interdisciplinary approach was central. Bringing these data together is already a research in itself, especially since archaeological and related dendrochronological data are far from complete and full of gaps (slide06). The dataset was created through coincidences and directed research, so it contains a lot of variation, both in time, spatial distribution and quantity.

Production of wood

First, let’s have a look at production. Wood is produced in a forest. In my research I have shown that there is clear evidence of forestry in Roman times (dia07). The knowledge to take care of trees is found in historical sources, such as planting, sowing and cutting, but fertilizing soil is also described in the ancient literature. At least four forestry systems were used in Roman times: clear-cutting, selection, coppicing and agricultural forest use. Clear-cutting is quite simple: all trees in a woodland were cut down. This could also be a military retaliation in Roman times, or simply a way to get a lot of wood. Selection involves the selection of specific trees for use and leaving some to stand. This is a way of management that we find in the historical sources, but also know archaeologically. Use of coppice certainly occurred, and has been shown archaeologically well before Roman times. In coppice, trees are cut or pollarded and the shoots are cut again after a number of years. Pollarded willows are a good example, but we also know of many oak coppices. The last forestry method that could be demonstrated in Roman times involves agricultural forest use, such as pigs being fattened in forests.

Provenance of wood

The provenance of wood was a central aspect of my dissertation. Whereas we know down to the centimeter where wood has been excavated, the growth location of trees is often unknown. I investigated this and developed a new method for this purpose. I used dendrochronological data. These are measurements of annual ring widths. For the most part, I did not measure these myself, but I was able to use measurements made by others. Fortunately, this data is now largely open, so it is reproducible and traceable. Why annual rings? The width of an annual ring is different every year, and this is due to differences in soil, weather and climate, among other things (slide08). Because each year is different, these patterns of wide and narrow rings are unique over time, making dating possible. In addition, these patterns are not only unique in time, they are also site-specific, because the growing conditions of trees in the western Netherlands, for example, are different from those in the Dutch sandy areas or towards Koblenz or Trier, for example. By comparing annual ring patterns, you can say something about similar origins. For that, however, you need a lot of data and I had that at my disposal.

Hadrian’s road

One of the provenance studies concerns wood from the limes road, or what I like to call Hadrian’s Road (slide09). This road was probably built in 125 AD with wood from trees cut down in the winter of 124-125. This road has been excavated at several sites, and both the construction method and the tree-ring patterns show that this was a centrally organized project. This was clearly one batch of timber, as the annual ring patterns of the oak posts from different sites are very similar, and thus came from the same region. My research has shown that the provenance area should be sought between Rhine and Meuse, near Xanten and Venlo (slide10). This provenance determination is based on the comparison with wood found in those regions, but also by the presence of cockchafer signal in the annual ring series. Depending on the region, grubs become cockchafers after 3-5 years. They then fly out and often eat the foliage of oak trees, severely limiting growth, which is reflected in the tree ring pattern. Cockchafers need a certain soil and that also corresponds to the provenance area I determined. The provenance in the Ardennes as assumed by others, by the way, is not correct.

Research on the limes road is based on the manual comparison of year-ring series. I essentially did the same in Chapter 6 of my dissertation, but for multiple case studies. This manual comparison works well in principle, but is time-consuming and not always easy to follow. Therefore, I wanted to find a way to make the research transparent, traceable and visual.

Similarity and networks

To determine the provenance and grouping needed in the large dataset used, I used multiple statistical measures. However, most studies often rely on one measure, but different measures sometimes just describe different aspects of the relationship. Unfortunately, a measure used since the 1940s, the Gleichläufigkeit, proved to be insufficient (slide11). I have therefore proposed a new statistical measure for measuring the degree of similarity: the “Synchronous Growth Changes” (SGC). This statistical measure is included in the standard dendrochronological software in R, dplR.

Clustering did not work adequately for grouping, because the data are distributed uneven in both time and space. I soon came up with the idea of exploring these statistical relationships through a network. Relationships are formed when the degree of similarity is strong enough (slide12). After all, if annual ring patterns have a strong statistical relationship, they will have had corresponding growing conditions and thus end up close together in the network. The locations in the network thus give an indication of origin. I did that and the networks show clear patterns (slide13). Especially when you start distinguishing groups, also called communities. To make this method more accessible and reproducible, I developed a piece of software (slide14): dendroNetwork (Visser 2024).

When interpreting provenance networks (slide15), one must consider the archaeological context and the systemic context. The latter refers to the use in the past. For example, a ship is likely to have sailed and moved. In addition, wood is more likely to have been transported downstream than upstream, and it is also more difficult to transport a tree up a mountain, rather than down. By comparing the spatial distribution of sites with the topology of the network, or appearance, you can thus make a good estimate of which wood was moved and which was not.

Model for the Roman wood provision

Based on provenance determination using the networks (slide16), it was found that most of the wood was procured locally. “Support your locals” is currently an imporant concept in relation to sustainability, in Roman times local procurement of wood was normal. However, I also found that in specific cases wood was obtained elsewhere, but as an exception. For example, I have already mentioned that for Hadrian’s road, wood was brought in over 100 kilometers away. Wood for the construction of various barges was also brought from elsewhere, from even further away, but in combination with locally obtained wood. For the harbor in Voorburg, wood was also brought from Upper Germania. In Roman times people made a very specific choice to get wood from elsewhere, but more often from local, or regional, forests.

I have tried to capture that in a model (slide17), which I described in two ways, as a pyramid and a circular model, please don’t confuse this with circularity. Local was the norm and was most common, hence that is the base of the pyramid. In the circular model, it is in the centre. Wood from further away, but still within the boundaries of the Roman province of Germania inferior, I have termed the provincial level. This also seems to be the maximum for the Roman army, which could possibly be related to the legal boundaries of the province. This is smaller in the pyramid and further from the centre of the circle. Wood brought in from outside the province is considered the imperial level. This was very exceptional, and therefore smaller in the pyramid. I have made the boundaries in the circular model fuzzy, because boundaries between the spheres are not always sharp.

Of course, I did a lot more, and of course all of it scientifically sound, open and reproducible, befitting open science. The dissertation itself and this presentation are also publicly available. Thank you for your attention and now to the committee’s questions. I wonder what questions they will ask me!